Heuristic evaluation of medical devices

Heuristic evaluation is a process which usability experts use to assess the usability of products by means of heuristics (explained in more detail below).

This article shows how you can use heuristic evaluations to meet the regulatory requirements of usability engineering very quickly and economically.

It also reveals why you should not restrict heuristic evaluation to the medical device or product itself.

1. Heuristic evaluation: disambiguation

a) Heuristics are not principles

A heuristic evaluation is a process which, as the name suggests, is based on heuristics. Heuristics are not synonymous with principles. A heuristic process is a rough rule of thumb, by means of which it is possible to reach a conclusion quickly and relatively accurately. In contrast, a principle is a ground rule that always applies.

Fig. 1: Heuristics versus principles. Heuristic evaluation not only uses heuristics but often uses principles and other style guides as well (see Table 1)

ISO 9241-110 mentions the seven design principles:

- Suitability for the task

- Self-descriptiveness

- Conformity with user expectations

- Suitability for learning

- Controllability

- Error tolerance

- Suitability for individualisation

b) Heuristics are not specific design rules

In usability engineering a distinction is made between heuristics and principles, and design rules and conventions.

Level | Example of description | Example | Typical source |

1. Design principles | A ground rule that always applies. | The system shows the necessary information for the user in every situation (self-descriptiveness). | Standards (e.g. ISO 9241-110) |

2. Heuristics | A rough rule of thumb, which often (but not always) applies, and serves to achieve (or verify) the implementation of a design principle. | The system should have a help function. This heuristic process supports the “learnability” principle. This applies as a matter of principle, but is not always applicable. For instance, a ticket machine does not require a help function. | Standards and subject literature |

3. Design rules | A concrete rule that must, however, be able to be implemented in different ways. | Input fields for mandatory data must be able to be differentiated from input fields for optional data. | Standards and subject literature |

4. Established conventions | Established standard specifications with no room for interpretation |

| Manufacturers’ style guides (also standards to some extent) |

Table 1: Types of style guides (from the book by Geis and Johner “Usability Engineering als Erfolgsfaktor – Effizient IEC 62366- und FDA-konform dokumentieren”* [Usability Engineering as a Success Factor – Documenting in compliance with IEC 62366 and the FDA])

2. Examples of heuristics

a) Jacob Nielsen

Original list of heuristic processes

Jacob Nielsen developed a set of well-known heuristics back in the 1990s. These heuristics include, for example, the following:

- Visibility of system status

The system should always keep users informed about what is going on, through appropriate feedback within reasonable time. Examples of such feedback are progress bars or illuminated disc symbols in the status bar when Word is saving data in the background. - Match between system and the real world

The system should communicate in the users' language and display information in a natural and logical order. - Aesthetic and minimalist design

Dialogues should not contain information which is irrelevant or rarely needed. Every extra unit of information in a dialogue competes with the relevant units of information and diminishes their relative visibility.

See the full list of Norman Nielsen’s heuristics:

- Visibility of system status

- Match between system and the real world

- User control and freedom

- Consistency and standards

- Error prevention

- Recognition rather than recall

- Flexibility and efficiency of use

- Aesthetic and minimalist design

- Help users recognise, diagnose, and recover from errors

- Help and documentation

If we study these heuristics in more detail, we can see that they are made up of a combination of heuristics and design principles. ISO 9241-110 calls the latter “dialogue principles”:

- Suitability for the task

- Self-descriptiveness

- Controllability (corresponds to number 3 of Nielsen's heuristics)

- Conformity with user expectations (corresponds to number 4 of Nielsen's heuristics)

- Error tolerance (corresponds to number 5 of Nielsen's heuristics)

- Suitability for individualisation

- Learnability (corresponds to numbers 6, 9 and 10 of Nielsen's heuristics)

List of heuristics with design mistakes

The NNGroup has written an article on common design mistakes in software. In the usability tests performed by the Johner Institute, the 10 most common mistakes result in problems time and again.

- Poor feedback

- Inconsistency

- Bad error messages

- No default values

- Unlabelled icons

- Hard-to-acquire targets

- Overuse of modals

- Meaningless information

- Junk-drawer menus

- Proximity of destructive and confirmation actions. (This is especially highly relevant in the case of medical devices.)

b) ISO 9241 (family)

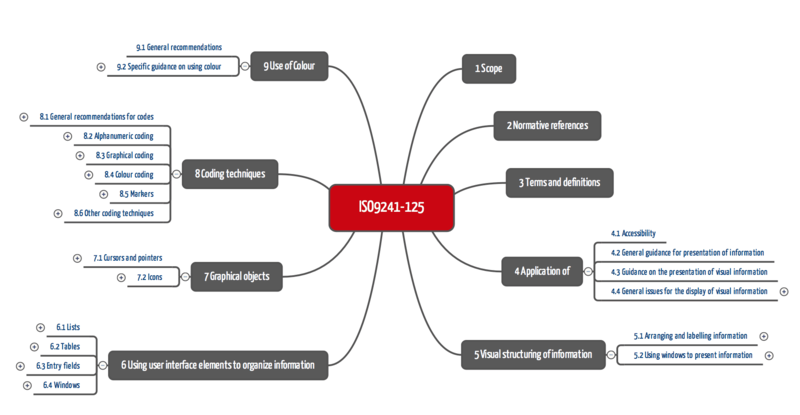

The ISO 9241 family of standards provides a very comprehensive collection of style guides (heuristics, design rules). For example, ISO 9241-125 explains how colours are to be used for coding, how cursors are to be designed, how and where labels are to be positioned and much, much more.

Further information

Read more about ISO 9241, as well as the specifications of ISO 9241-125.

Fig. 2: ISO 9241-125 mentions heuristics and rules for designing user interfaces (click to expand)

c) Examples of operating instruction tests

Operating instructions can also be tested with the help of heuristics and other criteria:

- Do the operating instructions refer to the right version of the product? Are they consistent?

- Is the language correct and comprehensible?

- Do the operating instructions describe the use from the point of view of the user (and not from the point of view of the developer)?

- Is the level of detail consistent and reasonable?

- Have the common measurement units of the corresponding “cultural environment” been used?

- Can the readers understand at all times where they are when reading?

- Does the list of contents enable fast navigation? Is there a list of key words?

- Do the operating instructions group together steps that belong together? These steps are all too often interrupted by descriptions of error messages and medical facts.

- Are there any instructions regarding troubleshooting?

- Are texts and images that belong together also presented together?

If more comprehensive operating instruction tests are possible, they are performed based on the criteria of IEC 82079-1 and AAMI TIR 49.

3. Heuristic evaluation: scopes of application

a) Formative evaluation

Heuristic evaluation is above all offered in the case of formative, i.e. development-accompanying, evaluation of user interfaces. It enables relevant user problems to be identified quickly and economically.

However, heuristic analysis is not suitable for proving the usability of user interfaces. To do this, it requires participatory observations, i.e. from usability testing.

b) Not only for the products themselves

Tip

Do not just evaluate the products with heuristic evaluation but also the operating instructions and other labelling elements.

c) In the case of company takeovers

Sometimes the procedure can also be applied for products that are already on the market. For example, a company that takes over a manufacturing company and its products would be able to quickly acquire an initial appraisal of their usability.

d) In the case of legal proceedings

Before the courts or in the event of disputes with the FDA, experts use heuristics to make statements about the usability of products.

5. Heuristic evaluation: procedure

A heuristic evaluation regularly involves the following steps:

- Establishing the object and aim of the evaluation

The manufacturer establishes the object (e.g. product, operating instructions) and objective (e.g. to obtain input for improvement/further development). - Planning and preparing for heuristic evaluation

The manufacturer determines the number of inspectors/usability experts. In the simplest case this is one person, ideally it is five. They select these people based on their qualifications and arrange appointments. During this step they also plan budgets and costs. - Performing the evaluation

The manufacturer presents the product and the objective of the heuristic evaluation to the experts. Less competent manufacturers in particular leave selecting the test criteria (heuristics, design rules) against which the evaluation is to be performed to the experts.

The experts examine the products individually and document the results, mentioning the design rules that are infringed, as well as any likely user problems. - Consolidating results

The experts consolidate their results and put forward suggestions for improvement. - Drawing final conclusions

The manufacturers analyse and assess the risks resulting from the anticipated user problems and decide which suggestions for improvement are to be implemented and how.

6. Pros and cons of a heuristic analysis

As with every process, heuristic analysis has its pros and cons.

Pros | Cons |

|

|

7. Standards and laws concerning heuristic processes

a) IEC 62366

TR IEC 62366-2 explicitly mentions heuristic analysis as one of the processes of formative evaluation. It describes this process in annex E11. The technical report even mentions heuristic evaluation in the context of assessing risk control measures.

However, the description of heuristic analysis is only four sentences long. “Only” these points are worth mentioning:

- one or more experts should participate (“perhaps three”);

- the experts should specify the problems and put forward suggestions for improvement;

- the experts should bring together their results (“develop consensus finding”) and document them; and

- the technical report mentions the work of Zhang and the standard AAMI HE 75 as sources for heuristics.

b) FDA

In the guidance document on human factors and usability engineering the FDA also goes into heuristic analysis:

- this process can/should be used to identify critical (safety-related) tasks;

- experts should be involved who evaluate against principles (sic!), rules or “heuristic” guidelines. The most suitable heuristics should be chosen. The document does not say what criteria should be used to select them; and

- the aim is to identify any possible weaknesses in the design, particularly if they could lead to harm.

The description of the process is also just a few sentences long in this guidance document.

8. Conclusion and summary

The concept of heuristic evaluation can often be a grey area, including in Wikipedia. Many sources not only understand it to be a test of usability by experts using heuristics. Rather, they apply all design rules and principles as test criteria.

That heuristic evaluation should be used above all as a process in formative evaluation is true. However, as mentioned above, there are also cases that go beyond this.

Heuristic analysis depends crucially on the competence and availability of experts. These experts should also originate from same environment as the future users in terms of language and culture. A German expert can only carry out provisional tests on operating instructions for the US market and vice versa.

If these requirements are met, manufacturers have a powerful and extremely economical, time-saving method on hand to be able to detect usability problems early and react to them.

Support and further information

Literary sources

In the article by Theresa Neil you can find great examples of how Nielsen’s heuristics are implemented in software applications.

t3n magazine has written an article about rules, patterns and dark patterns (No english version available) in usability engineering.

Worth a read is Zhang’s article “Using usability heuristics to evaluate patient safety of medical devices”.

Implementation

In their usability labs in Germany and the USA, the Johner Institute also supports manufacturers with heuristic evaluations and IEC 62366-1 and FDA-compliant documentation.