ISO 17664 - Processing of Medical Devices

The title of DIN EN ISO 17664:2018 is “Processing of health care products — Information to be provided by the medical device manufacturer for the processing of medical devices.”

However, the standard doesn’t just deal with the “information to be provided”, it also looks at the activities and processes involved in processing.

This article explains what the MDR requires that the MDD doesn’t, what every manufacturer should know about the processing of medical devices and when ISO 17664 does not apply.

1. Introduction to the world of ISO 17664

a) Definition of terms

Definition: processing

“Cleaning, disinfection and sterilization to prepare a new or used healthcare product for its intended use.”

Source: ISO 17664

The definition of “reprocessing” in the MDR is similar:

Definition: reprocessing

“‘Reprocessing’ means a process carried out on a used device in order to allow its safe reuse including cleaning,

disinfection, sterilisation and related procedures, as well as testing and restoring the technical and functional safety of the used device.”

Source: MDR Article 2(39)

Definition of “cleaning”

The standard also defines the terms cleaning, disinfection and sterilization.

Definition: cleaning

“Removal of contaminants to the extent necessary for further processing or for intended use.”

Source: ISO 17664

The standard comments that “cleaning consists of the removal, usually with detergent and water,

of adherent soil (e.g. blood, protein substances, and other debris) from the surfaces, crevices,

serrations, joints, and lumens of a medical device by a manual or automated process that prepares the items for safe handling and/or further processing.”

Definition of “disinfection”

Definition: disinfection

“Process to reduce the number of viable microorganisms to a level previously specified as being appropriate for a defined purpose.”

Source: ISO 17664

The standard does not add any notes for this definition.

Definition of “sterilization”

Definition: sterilization

“Process used to render product free from viable microorganisms”

Source: ISO 17664

In this case, ISO 17664 does add a note to the definition: “In a sterilization process,

the nature of microbial inactivation is exponential and thus the survival of a microorganism on an individual item can be expressed in terms of probability.

While this probability can be reduced to a very low number, it can never be reduced to zero.”

Summary

These definitions make it clear how the different processing procedures result in a different “levels of cleanliness”.

In terms microorganisms, a distinction is made between:

- Bacteria, e.g., coliforms, staphylococci, pseudomonads

- Fungi and yeasts

- Parasites e.g., worms, amoebas, giardia lamblia

- Nonenveloped viruses (hepatitis A, rotavirus, adenovirus, norovirus) and enveloped viruses (HIV, influenza, TBEV, corona virus)

Note: The MDR uses the term “reprocessing” and gives it a broader definition than ISO 17664 does to “processing”. It also defines the terms “fully refurbishing ”, which does not necessarily have to be a special type of processing according to ISO 17664.

b) Examples of devices that have to be processed

A lot of single-use medical devices, such as cannulas, surgical gloves and plasters, must be processed, or to be more precise sterilized, before they can be used. This processing is usually performed by the manufacturers or their service providers.

However, reusable medical devices, such as bedpans, surgical gowns, surgical instruments (e.g., scalpels) and medical equipment (e.g., ventilators), must also be cleaned and, if necessary, disinfected or even sterilized before being used again. This also applies for endoscopes, patient supports and handpieces for dental instruments.

N.B!

A lot of the devices named in this section do not fall within the scope of ISO 17664.

This (re-)processing is usually performed by healthcare providers (e.g., hospitals) or their operators.

c) Scope of ISO 17664

ISO 17664 does not take responsibility for all medical devices. It does not apply to:

- Non-critical medical devices

- Textiles (e.g., surgical clothing)

- Single-use medical devices that are supplied in sterile condition (e.g., cannulas)

The standard defines the criticality categories in the informative Annex C:

Device criticality | Definition: Devices... | Example |

Not critical | … come into contact with intact skin or are devices that are not intended for direct patient contact | Blood pressure cuffs, bedpans, crutches and surrounding surfaces |

Semi-critical | … come into contact with mucous membranes or non-intact skin | Anesthesia systems, ventilators |

Critical | … usually penetrate sterile parts of the human body | Surgical instruments, implants, invasive medical devices |

The standard only takes responsibility for single-use devices that are only processed, i.e., cleaned, disinfected and, if applicable, sterilized, after they have been supplied.

ISO 17664 was limited to the sterilization process and resterilizable medical devices before the current version was published in 2017. Now it also includes medical devices that are cleaned and disinfected.

d) Who is the standard aimed at?

The title of the standard (“[...] Information to be provided by the medical device manufacturer [...]”) makes it clear who it is aimed at: manufacturers. It is, therefore, not directly aimed at healthcare institutions or users. Rather these groups are the people receiving the manufacturer's information.

e) Objective of ISO 17664

It shouldn’t be surprising that ISO 17664 has patient safety in mind. However, it wants to contribute more than just minimizing infectious agents towards achieving this safety.

It also wants to reduce other detrimental effects on the medical device caused by processing. Examples of this would be a reduction in its service life or a loss of other general safety and performance requirements due to processing.

2. Regulatory requirements for processing

a) EU Medical Device Regulation (MDR)

Article 17 (“Single-use devices and their reprocessing”)

Article 17 essentially deals with the “reprocessing and further use of single-use devices”. In other words, it does not regulate the initial processing of single-use devices.

Article 17 defines all natural and legal persons who reprocess single-use devices to make them suitable for further use as manufacturers. All the obligations that apply to manufacturers apply to these people accordingly.

Annex I, paragraph 23.4 (“Information in the instructions for use”)

Annex I, which sets out the general safety and performance requirements, also contains the requirements for the instructions for use, which must include the following information:

“if the device is reusable, information on the appropriate processes for allowing reuse, including cleaning, disinfection, packaging and, where appropriate, the validated method of re-sterilisation appropriate to the Member State or Member States in which the device has been placed on the market. Information shall be provided to identify when the device should no longer be reused, e.g. signs of material degradation or the maximum number of allowable reuses.”

MDR, Annex I, Chapter III, 23.4 n)

The MDR also requires manufacturers to describe exactly how the users:

- Should reprocess the devices

- Can tell if the device is still suitable for reprocessing

The next requirement is also concerned with this:

“if the device is a single-use device that has been reprocessed, an indication of that fact, the number of reprocessing cycles already performed, and any limitation as regards the number of reprocessing cycles.”

MDR, Annex I, Chapter III, 23.4 o)

b) EU Medical Device Directive (MDD)

The MDD's requirements were very similar. According to MDD, the instructions for use must include:

“(h) if the device is reusable, information on the appropriate processes to allow reuse, including cleaning, disinfection, packaging and, where appropriate, the method of sterilization of the device to be resterilized, and any restriction on the number of reuses.

Where devices are supplied with the intention that they be sterilized before use, the instructions for cleaning and sterilization must be such that, if correctly followed, the device will still comply with the requirements in Section I;

(i) details of any further treatment or handling needed before the device can be used (for example, sterilization, final assembly, etc.)”

MDD, Annex 1, paragraph 13.6

Annex ZA confirms that confirms that conformity with “13.6 h, first and second sections only” and 13.6 I may be presumed by compliance with EN ISO 17664.

c) ISO 10993-1

In addition to European legislation, there are also standards that are related to ISO 17664. For example, ISO 10993-1 contains several sections that require manufacturers to check the influence of processing:

- 7 “The biological safety of a medical device shall be evaluated by the manufacturer over the whole life-cycle of a medical device.”

- 4.5.1 “Typical changes that could alter the biological performance of a material or final medical device include, but are not limited to: processing e.g. sterilization, cleaning, surface treatment, welding, injection moulding, machining, primary packaging;”

- 8 “For re-usable medical devices, biological safety shall be evaluated for the maximum number of validated processing cycles by the manufacturer.”

Further information

Read more on the biocompatibility and ISO 10993 here.

3. The ISO 17664 standard:

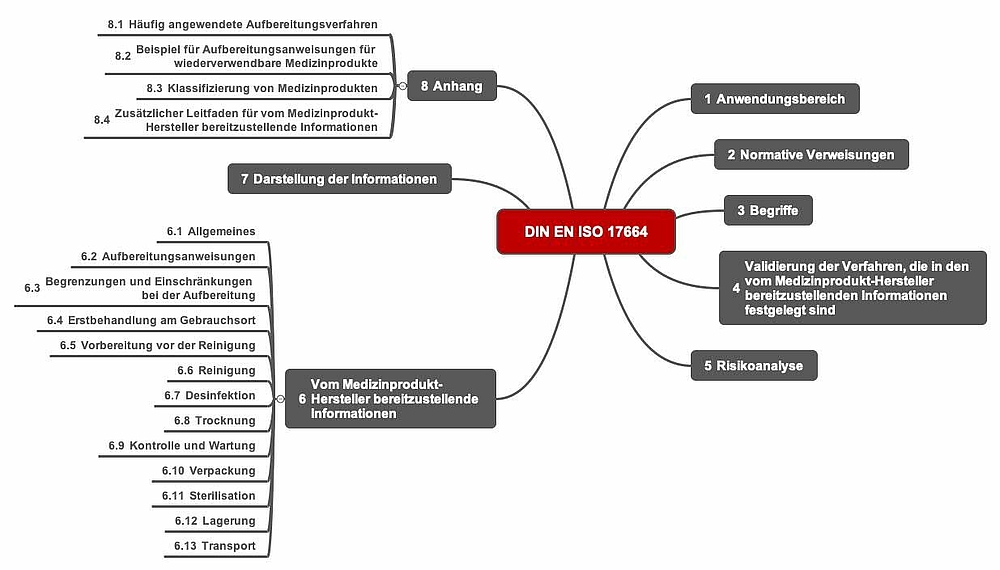

a) Structure of the standard

The standard is relatively slim at just 36 pages and the fourth and fifth sections together only take up a single page. The sixth chapter is eight pages long, the seventh not even a quarter of a page.

The informative annexes, which together are 10 pages long, are very helpful.

b) Requirements

ISO 17664 requires manufacturers to:

- Validate the processing

All medical device processing procedures must be validated. The standard does not specify how manufacturers should carry out this validation. - Analyze the risks from processing according to ISO 14971

The manufacturer must conduct a risk analysis in accordance with ISO 14971. Manufacturers must factor all the typical processing steps (see below) into this risk analysis. They must then determine the information that needs to be provided based on this analysis. - Provide information

The information to be provided must include the elements specified in section 6 for all processing steps.

A typical processing procedure contains several steps (see Fig. 5).

ISO 17664, for example, requires information including the following to be provided for manual cleaning:

- Step-by-step cleaning instructions

- The chemicals to be used and their concentration

- Contact time of the chemicals

- Water quality required

- Type of rinsing

- Other process parameters

c) ISO 17664-2: New second part for non-critical devices

A second part of the standard - ISO/DIS 17664-2:2019-05-Draft - is available as a draft. Its title is “Processing of health care products — Information to be provided by the medical device manufacturer for the processing of medical devices – Part 2:Non-critical medical devices”.

This part is intended the close the gap that meant that non-critical medical devices were not covered (see Fig. 3). It applies to both single-use medical devices and the reuse of medical devices.

Examples of such devices would anesthesia equipment, parts of an ultrasound machine, blood pressure devices, ECG cables, handles of surgical lights.

ISO 17664-2 contains information on the effective processing of non-critical devices without sterilization. It provides a flow chart to help you decide whether a devices falls within the scope of ISO 17664-1 or ISO 17664-2.

4. Eight practical tips for implementing ISO 17664

Tip 1: Think about processing even in the design stage

Manufacturers should already be keeping an eye on processing even in the development stage. They should pay particular attention to the:

- Choice of geometry

Areas that are hard to reach must be avoided so that cleaning, disinfection and sterilization can be performed more easily. This affects, for example, cavities (bag lumens, thin lumens), open mechanisms and transitions (edges, seams). - Requirements resulting from processing

If there are areas that cannot passively be reached by detergents and disinfectants, these areas must be actively rinsed (e.g., consider rinsing connections in the design phase). - Choice of materials

Choosing the right materials in crucial in two ways: Firstly, they must easy to process. Secondly, they must be able to survive a lot of processing cycles without compromising mechanical or biological safety. For example, materials that become porous are more difficult to clean, disinfect and sterilize. - Choice of processing procedure

A lot of developers design their devices based on its intended purpose in order to optimize its benefits. The choice of processing procedure takes a back seat. In general, mechanical processing is always preferable. Mechanical processing can have consequences for the design of the device.

Tip 2: Consider biocompatibility risks in two regards

A lot of manufacturers “only” analyze the risks resulting from a user not performing a processing step in accordance with the specifications and, therefore, the cleanliness requirements not being met.

But manufacturers should also consider the risks that are present even if the processing is performed according to the specifications. So they should test detergents and disinfectants for critical ingredients.

Special tests make it possible to sufficiently demonstrate the biocompatibility of detergents and disinfectants.

Unfortunately, not all the ingredients are always listed on the safety data sheet (see the comment in Annex D of DIN EN ISO 17664).

N.B!

Notified bodies are increasingly asking how it is ensured that no production residues

(e.g., of process chemicals) remain on the device. If the process chemicals were defined and controlled more precisely,

this would be less of a problem or even not a problem at all.

Tip 3: Check the completeness of the design output

The “design output” should include the:

- Definition of the design and geometry, design drawings

- Specification of all materials If necessary, definition of alternatives for the purchasing department

- Precise specification of the processing procedure, including all work steps, process parameters and cleaning materials

- Definition of the number of processing cycles and/or lifetime and/or the criteria to determine whether a device can be reprocessed.

- Risk management file

Tip 4: Work with device families rather than individual devices

Medical device manufacturers should make use of the option to take the whole device family into account rather than each individual device. This saves redundant and thus unnecessary time and costs, e.g., when it comes to demonstrating biocompatibility.

Worst case scenarios have been proven to be successful. Worst case refers, e.g., to:

- Risks for patients due to inadequate processing

- Unsuitable process parameters during processing

- Probability and nature of possible use errors

- Geometry of the device

- Type (microbes), place and degree of contamination of the device

Tip 5: Select a suitable testing laboratory

Manufacturers would be well advised to select a testing laboratory that, together with them:

- Has specific experience with medical devices

- Takes a risk-based approach and does not try to maximize its revenues

- Can estimate what the worst case devices that have to be tested are for the given product family

- Is able to create test protocols that comply with standards

- Can validate the processing and(!) processing instructions

- Has experience of evaluating the effects of inadequate processing as well as the effects of the detergents and disinfectants on biocompatibility

Tip 6: Avoid typical validation errors

The experts at the Johner Institute often see manufacturers making the same mistakes during validations:

- Unsuitable test soiling

The testing laboratory does not actually test the worst case scenario with regard to the device (from a device family), the choice of microbes, location of soiling (especially for critical geometries). - Incomplete risk analysis

The manufacturer or the laboratory does not analyze the risks associated with the choice of detergents and disinfectants. In particular, their effects on the service life of the device are not systematically investigated and documented. The same applies for risks from detergent and disinfectant residues. - Lack of usability assessment

Testing laboratories evaluate whether the processing instructions are suitable. However, they do not evaluate their àusability and potential use errors. - Lack of revalidation

The device’s biocompatibility also has to be reassessed in the event of changes to the final cleaning, cleaning, disinfection and sterilization, not just in the event of changes to the device design.

Tip 7: Distinguish between different validations

Auditors and quality managers should ensure and check that they have the following understanding:

A validated final cleaning does NOT replace the need for the processing to be validated. This is because the detergents used target other residues. We see residues from production that cause problems even after processing on devices again and again.

A validated processing is therefore no guarantee of a “clean” medical device that is free of residues from the production process. In addition, detergent residues can build-up in hard-to-reach parts of the device over the device's lifetime.

Validated processing does NOT replace verification of biocompatibility. Due to a potential build-up of residues and potential material changes (brittleness, corrosion, etc.), an “end of life” has to be defined. This is only possible if biocompatibility is taken into consideration.

Tip 8: Avoid unnecessary tests

The verification of biocompatibility does not usually require animal testing. Please read the article on biocompatibility to see how to avoid unnecessary tests, regulatory problems and risks to patients.

5. Conclusion

Since processing includes the cleaning of devices, not just their disinfection and sterilization, a lot of manufacturers have to comply with ISO 17664 and other standards.

ISO 17664 is a compact and easy-to-understand standard. Its scope is currently limited to semi-critical and critical devices. It also excludes single-use devices that are supplied in a sterile condition. ISO 17664-2 extends the scope of the standard to include non-critical medical devices.

To ensure legally compliant processing and, thus, patient safety, manufacturers must take into account their device’s complete lifetime: from the device specification, to the device design, through to the definition and establishing of the device's “end of life”.

Manufacturers try to minimize the risks caused by a lack of biological safety through processing. At the same time, they should keep an eye on the risks caused by a lack of biocompatibility resulting from the processing in particular.

Choosing the right validation strategy helps to avoid unnecessary costs without compromising regulatory compliance and patient safety.

6. Support

The Johner Institute offers support to manufacturers for all activities, not just in the context of ISO 17664:

- Evaluation of the device design (geometry, materials)

- Definition of the service life

- Processing specification

- Wording and design of the processing information

- Formative and summative assessment of usability

- Risk analysis

- Writing of validation plans

- Performance of validation

- Selection of testing laboratories