Software as Medical Device: Definitions and Classification Aids

With software as medical device, it differentiates between standalone software and software that is part of a medical device. Classifying the standalone (also called SaMD - Software as Medical Device) software is often difficult, especially whether it is classified as a medical device.

- Who decides whether a software should be classified as a medical device

- When is a software classified as a medical device

- Publications and decision support by authorities

- Examples of software as a medical device (web pages, web services, KIS)

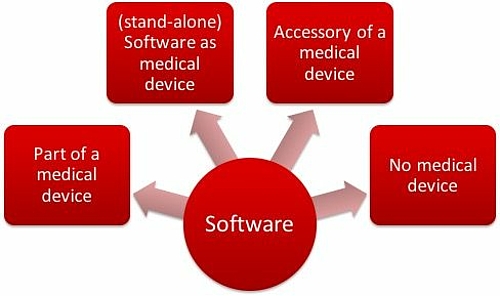

Software in medical product field will be classified as

- Software as a part of a medical product e.g. as embedded software of a medical device

- Software as medical product itself (standalone software)

- Software as accessories of a medical product

- Discrete software, that is not a medical product

Depending on this classification, manufacturers must pay attention to the different regulations. This article helps you to classify your own software.

B) Classification of Software as a Medical Device: Who Decides

Manufacturers and authorities are often experiencing uncertainty regarding if a software is classified as a medical product or not. This is also the reason why many decision-making aids are published, present below.

The decision on whether a software should be classified as a medical device is up to the manufacturer themselves. Notified Bodies can provide advice. But the advice that the manufacturer attained does not give any legally binding information. Inquiries for the BfArM will not usually be answered promptly. Ultimately, and this may sound cynical, a judge will only answer this question in the case of a lawsuit for the classification of software as a final medical device.

For this, the judge will appoint an appraiser. They will, by examining the writing of the report, test if the software corresponds to the definition of medical device; in other words if it serves (to formulate it briefly) its diagnosis, treatment or monitoring of diseases and injuries.

If you have software of which you are unsure of, then please contact:

- The Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (but response time is not always quick - to put it mildly)

- Notified bodies. Here I can give you some contacts

- As for us, we constantly respond to such questions. Fast and efficiently.

C) Software as Medical Device: Decision Guidance for Classification

The issue of "classification of software as a medical device" preoccupies not only the manufacturers of medical devices, but also the authorities, bodies and associations. They have published a number of documents about this, which should serve as decision aids.

- COICR Contribution

- EU: Manual on Borderline and Classification

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency

- IMDRF

- MEDDEV 2.1.6

- Swedish Authorities

- Asian Harmonization Working Group

- The FDA on the Classification of Software as a Medical Device

- Health Canada

- MDCG

- Australia

1. COICR Contribution

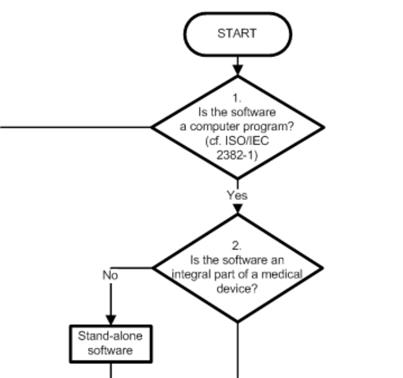

The "European Coordination Committee of the Radiological, Electro-medical and Healthcare IT Industry" has published a "Decision Diagram for Qualification of Software as Medical Device".

I'm still a little hesitant, as to what I should make of it. On the one hand there is nothing really new in it (and ultimately only the legal definition counts), on the other hand people have done the work here to support us manufacturers and developers.

2. EU: Manual on Borderline and Classification

From the EU comes a "Manual", that tries using examples to distinguish medical from non-medical devices and to give help in classification. The examples relate partly to Software:

- Picture Archiving and Communication Systems

- A mobile application for processing ECGs

- A mobile application for the communication between patient and caregivers while giving birth

- A mobile medical application for viewing the anatomy of the human body

3. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency

Next, the British "Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency" issued a document entitled "Borderlines with Medical DDevices". In Chapter 9 of the document you can read the sentence on the "Telecare Alarm System".

4. IMDRF

Now there's a document from the International Medical Device Regulator Forum IMDRF. It defines the terms

- Software as a Medical Device (SaMD)

- Medical Device

- Invitro Diagnostic Medical Device

- SaMD Changes

- SamD Manufacturer

- Intended Use / Intended Purpose

The document is pleasantly short with just 10 pages and definitely worth a look.

An interesting feature of this article is the fact that on the one hand it largely limits itself to definitions of terms, but on the other hand it makes use of already existing concepts or just repeats them. A distinction between a "SAMD Manufacturer" and "Manufacturer" does not result from this. What could be the value of this? Perhaps the realization that software is not to be treated differently.

Particularly interesting for me were the references and among other things the sources:

- GHTF/SG1/N55:2008 Definition of the Terms Manufacturer, Authorized Representative, Distributor and Importer

- GHTF/SG1/N70:2011 Label and Instructions for Use for Medical Devices

- GHTF/SG1/N71:2012 Definition of Terms Medical Device and In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Device

- ISO/IEC 14764:2006 Software Engineering — Software Life Cycle Processes —Maintenance

The IMDRF explains the definition of a medical device again and lists cases in which a stand-alone software does not count as part of a medical device, and when it does, such as:

- mitigation of a disease,

- provide information for determining compatibility, detecting, diagnosing, monitoring

- or treating physiological conditions, states of health, illnesses or congenital deformities,

- aid in diagnosis, screening, monitoring, predisposition, prognosis, prediction, determination of physiological status.

- aids for persons with disabilities

Whether these are really groundbreaking insights into the classification of software as a medical device is debatable. Finally, the support is not critical beyond the classification of the definition of medical devices.

5. MEDDEV 2.1.6

The MEDDEV 2.1/6 has released the document Guidance on the Qualification and Classificastion of Stand Alone Software used in Healthcare within the Regulatory Framework of Medical Devices. But it has never progressed beyond the draft stage. One divides software into the following categories:

- Software which is not a medical device, such as development tools or documentation systems, which include the KIS. But only as long as they are not for diagnosis or treatment.

- Software as a component of a medical device, as in the device software.

- Software, which is a medical device. There are four subclasses:

- Software that is explicitly mentioned in one of the directives as a medical device - as in the directive for in-vitro diagnostic software

- Software which influences or controls medical devices, such as software for the planning of radiotherapy

- Software with a "view to diagnosis and monitor", such as software for the evaluation of long-term ECG signals or the measurement of anatomical measurements in a radiograph.

- Software, which is used for or through the patient for the diagnosis. For example, an application is mentioned, with which Attention Deficit Disorder ADHD can be diagnosed.

6. Swedish Authorities

From the Swedish authorities comes the „Medical Information Systems – guidance for qualification and classification of standalone software with a medical purpose“.

7. Asian Harmonisation Working Group - Software Qualification and Classification

The Asian Harmonisation Working Group Document repeats the definitions in the context of "Software as a medical product" as a "stand alone software", "Mobile Medical Application" and "Health Programs" and distinguishes three types:

- Software that is part of a medical device (often referred to as embedded software)

- (standalone) software that is an accessory for a medical product such as for forwarding data

- Standalone software, which is a medical device itself (Software as a Medical Device SAMD) that is provided either on disk or via download or as a web-based software.

Furthermore, the document introduces already existing considerations, for the classification of software as a medical device and essentially discusses the above mentioned sources:

- The publication of the IMDRF (see above)

- The Australia "Therapeutic Goods Association" (TGA) referenced itself against European and American publications. It classifies documentation software and software, which only do simple calculations, that are not based on patient-specific data, as not a medical device. If the software controlled or influenced another medical device, it falls into the same class.

- The Chinese Food and Drug Administration CFDA have a precise policy for the registration of software published as a medical device, in turn, the security classification in accordance with IEC 62304 is used.

- In the documents published in Europe the MEDDEV 2.1 / 6 (see above) is mentioned, as well as some tabulated examples of software that would be classified as a medical device or as a non-medical device. The classification rules set out in Appendix IX of the MDD are also cited.

- The document briefly discusses the requirements of Health Canada and mentions above all a FAQ document which gives examples and rules for the classification of software as a medical device. Again a chart mentions concrete examples.

- Among the requirements of the Japanese MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare) is written, that standalone software may be a medical device and that further recommendations are just about to be worked out.

- An overview of the specifications of the FDA (see above) completes the series of the investigated areas of law.

In the summary, the document summarises the similarities and differences, among other things, in a table. Herby, software is discussed, which serves data communication. This software is not classified in Europe as a medical product, but it is already in most other areas of law.

10. The FDA on the Classification of Software as a Medical Device

a) Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C)

In the summer of 2017, the US Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C for short) revised the term “medical device” specifically with regard to software. However, this description was so cryptic that the FDA felt compelled to publish a guidance document in December 2017 setting out its interpretation of the law. Although this guidance document only refers to the decision support systems, it can easily be transferred to other standalone software.

In September 2019, the FDA published a guidance document on “Changes to Existing Medical Software Policies Resulting from Section 3060 of the 21st Century Cures Act”. In this guidance document, the FDA again set out its interpretation, provided examples and referred to other guidance documents, some of which are mentioned below.

b) General Wellness: Policy for Low Risk Devices

The Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act was revised at the end of November 2016. It no longer(!) defines software used “for maintaining or encouraging a healthy lifestyle and [that] is unrelated to the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition” as a medical device.

The FDA confirms in Guidance document “General Wellness: Policy for Low Risk Devices” that it does not intend to examine “low risk general wellness products” to determine whether they are medical devices nor does it intend to examine, if they are classified as medical devices, whether they comply with the regulatory requirements.

But the prerequisites for this are:

- The devices must be intended exclusively for general wellbeing (“wellness”), as defined in this document.

- The devices must be low risk.

Manufacturers must not make any reference to diseases to be diagnosed or treated with the devices. Instead, the device must relate to, for example:

- Weight management (but not(!) the treatment of obesity)

- Physical fitness

- Stress management

- Sleep

However, the FDA also allows devices related to certain diseases in this category if they could help:

- Minimize the risks of certain chronic diseases.

- Patients to live better with certain chronic diseases.

The guidance document gives examples and provides a small decision tree.

Conclusion: Through this document, the FDA has provided clarity as to when devices - including software - are exempted from FDA inspection. This is what people in Europe want. The FDA also exempts a lot more devices from inspection than European authorities and regulators do.

c) Policy for Device Software Functions and Mobile Medical Applications

The guidance on mobile medical apps published in 2016 defined apps that:

- Are not medical devices

- Are medical devices, but are not inspected by the FDA

- Are medical devices subject to FDA inspections

With its 2019 update, the FDA has extended the scope to other software and now often talks about “software functions”. Mobile apps are only one type of software that has such functions.

This means that you should consult the document even when you have to decide whether software that is not a mobile medical app is a medical device or not.

d) FDASIA Report

The FDA is co-editor of the FDASIA Report. FDASIA stands for Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act, an act that required the FDA to prepare a report

“that contains a proposed strategy and recommendations on an appropriate, risk-based regulatory framework pertaining to health information technology, including mobile medical applications, that promotes innovation, protects patient safety, and avoids regulatory duplication.”

In this report, the FDA again distinguishes (as in the guidance document on mobile medical apps) between:

- Non-medical devices

- Medical devices for which the FDA requires compliance with legal requirements (e.g., approval procedures, quality systems regulations) and

- Medical devices for which it does not.

This division into three is surprising. It means laws don't always have to be obeyed?! The FDA justifies this differentiation with a “risk-based approach”:

“In applying a risk-based approach, FDA does not intend to focus its regulatory oversight on these products/functionalities, even if they meet the statutory definition of a medical device.”

It also gives concrete examples in which it considers these exceptions to be justified:

- Evidence-based clinician order sets tailored for a particular condition, disease, or clinician preference;

- Drug-drug interaction and drug-allergy contraindication alerts to avert adverse drug events;

- Most drug dosing calculations;

- Drug formulary guidelines;

- Reminders for preventative care (e.g. mammography, colonoscopy, immunizations, etc.);

- Facilitation of access to treatment guidelines and other reference material that can provide information relevant to particular patients;

- Calculation of prediction rules and severity of illness assessments (e.g., APACHE score, AHRQ Pneumonia Severity Index, Charlson Index);

- Duplicate testing alerts;

- Suggestions for possible diagnoses based on patient-specific information retrieved from a patient’s EHR.

It is not quite clear what statistical analysis the assumptions that the above device classes present fewer risks are based on. Such clinical decision support systems are often particularly treacherous because the risks are not as obvious as they are with classical medical devices such as ventilators.

A new guidance document gives concrete examples of when software no longer has to be classified as a medical device:

- Software for administrative support

- Laboratory information systems (as long as it is only used for administrative support, storage, transport and conversion of laboratory data)

- Software intended to encourage a healthy lifestyle, e.g., an app that records and displays movement, or an app that warns the user if they eat too much or unhealthily. Diaries and social games are other examples.

- Electronic patient records, but only if three conditions are met:

- They are created by or under the supervision of healthcare professionals

- They are not subject to the Health IT Certification Program

- They are not intended for the analysis of patient records, including medical image data, for the purpose of the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment.

- Software that is only used to forward, save, convert and display laboratory data and other device data, provided that this data is not analyzed. This means that medical device data systems are no longer medical devices. PACS are also no longer considered medical devices.

The FDA will have to revise the aforementioned guidance documents accordingly.

Further information

You can read more about this in this draft FDA guidance on “Existing Medical Software Policies”.

11. Health Canada

Health Canada has published a Draft Guidance Document - Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). It is essentially based on the aforementioned IMDRF framework and adopts its definitions. It adds to these ideas with examples.

a) Medical purpose

Health Canada gives examples of medical purposes:

- Acquiring, processing or analyzing medical images

- Acquiring, processing or analyzing information from an IVDD

- Acquiring, processing or analyzing information, measurements or signals from a monitoring or imaging device

- Supporting or providing recommendations for patients or health care professionals regarding prevention, diagnosis, treatment, or mitigation of a disease or condition

However, Health Canada does not classify all systems designed to help decision-making as a medical device.

b) Examples of software that is not a medical device

Health Canada also helps by giving some examples of software that it does not consider to be medical devices:

- Pure communication systems such as MDDS, telephones, etc.

- Software used solely for administrative purposes, including workflow, patient management, scheduling

- Software intended to encourage a healthy lifestyle, such as wellness apps

- Electronic patient records

- Software that provides access to literature data

- Software that warns of drug interactions

- Software that does not trigger any immediate actions

- Software for simple medical calculations

c) Risk classification

Health Canada also takes the IMDRF document as the basis for risk classification, but permits a lower classification in some places.

12. MDCG

Overview

The MCDG 2019-11 document governs the classification of medical device software according to the MDR. It replaces the aforementioned MEDDEV 2.1/6. The classification scheme is key for a lot of manufacturers:

The last question, “Is the Software a Medical Device Software according to the definition of this Guidance?” is particularly relevant. As a reminder:

Medical device software is software that is intended to be used, alone or in combination, for a purpose as specified in the definition of a “medical device” in the MDR or IVDR, regardless of whether the software is independent or driving or influencing the use of a device.

MDCG 2019-11

The MDCG emphasizes that the following are irrelevant for classification as MDSW:

- Where the software runs (in the cloud, on a smartphone, on a server)

- Who uses the software (general public, healthcare professionals)

- Whether the software controls a medical device or not

- Whether the software runs as standalone software or is part of a medical device

Examples

The MDCG gives examples of such medical device software (MDSW):

- Standalone software that is used for diagnosis or treatment, including software to evaluate the risk of trisomy 21 in a child based on serum markers in the mother

- Software that calculates the risk of prostate cancer from ultrasound images, patient and laboratory parameters

- Mass spectrometry software used to identify microorganisms and detect their resistance to antibiotics from data

- Apps that send alarms to patients or doctors when they detect cardiac arrhythmia in the form of irregular heartbeats

- Software that measures glucose values and uses them to calculate insulin doses and drives an insulin pump (potentially even as a closed loop system).

- Cloud-based software that performs a point of care test

Further information

Read our article on when software as an IVDD This classification also applies to the MDCG document.

Exception: Software used only to control hardware

If a piece of software is used exclusively to control a medical device’s hardware and does not have its own medical purpose, then it should be considered only as part of this medical device. In this case, an additional classification according to Rule 11 does not come into consideration.

Criticism of the MDCG document

There has been criticism already, just a few days after publication. Antonio Bartolozzi published a presentation on LinkedIn:

MDCG 2019 11 Guidance on Qualification and Classification of Software MDR-IVDR from Antonio Bartolozzi

Criticism from Professor Bartolozzi

The Johner Institute assesses this criticism as follows:

- New and uncoordinated definition

It is true that the new definition of the term Medical Device Software (MDSW) is different from previous definitions. This can cause confusion. At the same time, this definition defines the actual concept that can and should(!) lead to software that is part of a physical medical device giving the whole medical device a higher classification. - New concept

Other areas of criticism in the presentation seem to be conditioned by the fact that the author does not want to accept the concept or does not understand it. But a definite definition and comparison of the concepts would have done the MDCG document good. - Binding nature of the MDCG document

Querying the legal force of the MDCG document is legitimate. In this case, rules have been laid down which are de facto interpreted as binding, even though they bypass parliamentary processes or other forms of consensus-building, such as standardization. Even ECJ judges have relied on such documents. - Examples

Prof. Bartolozzi also strongly criticizes the examples. Of course, hospital information systems will be used to obtain information for diagnosis and treatment. But that's not their purpose. It is therefore true that these systems are incorrectly classified. But it was not the job of the MDCG to regulate this.

Equally, you can agree that a PDMS is a medical device. The MDCG tries, somewhat unsuccessfully, to wiggle itself out of this one. - Inconsistencies

In reality, the classification of medical devices with identical intended purposes should not depend on whether the devices are considered software or hardware.

Conclusion: The criticism cannot be completely dismissed, even though in some places it is slightly over the top with several exclamation marks. Rule 11 is unsuitable in its current form and the MDCG document does not completely rectify this. That's partly because it:

- introduces new definitions and concepts without explaining and defining them sufficiently.

- twists existing concepts (e.g., IMDRF).

- is formulated in such a way that it would not pass a usability test.

- appears slightly arbitrary or contradictory with regard to existing rules in some places at least.

At the Johner Institute, we don’t think that the classification proposed by Mr. Bartolozzi is the solution either. It would mean that even more devices would fall into class III than is being proposed by the MDCG.

He himself argues that classification should be risk-based, but then takes Rule 11, which only considers the severity of the potential damage, as the basis for his classification.

13. Australia

The Australian TGA describes in a document titled “Exemption for Certain Clinical Decision Support Software Guidance on the exemption criteria” the circumstances under which a clinical decision support system is not subject to regulation.

This is the case when three conditions are met:

- The software is used solely to provide recommendations to health professionals for the diagnosis, prevention, cure and mitigation of disease and injury.

- It does not directly analyze or process medical image data or biosignals from other medical devices (including IVDs).

- It is not intended to replace the evaluation by health professionals regarding diagnosis or therapy.

There are many products that benefit from these facilitations.

D) Examples for software as a medical device

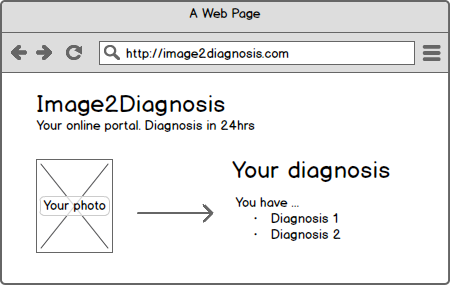

1. Website as a medical device

Heise Online reports of a start-up whose business idea is to diagnose skin diseases on the Internet and charge for this. The company (Goderma)’s website (goderma.com/) takes you through a questionnaire and allows to upload photos of your own skin. Within 48 hours you will get an answer. For just 29 EUR.

Without wanting to go into a discussion about which advantages and disadvantages such an offer has, the question arises whether a / this website is a medical device. Web pages can generally be medical devices - examples of which I have already mentioned in this blog. And what about the specific website? Does it also fall under the definition of a medical device?

To give you a shortened version, the 2007/47 has clarified that stand-alone software also falls under the definition of a medical device, when it can serve the diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of diseases and injuries. It seems likely that the website serves the diagnosis of the disease because Goderma offers the supply of the diagnosis of skin diseases.

Thinking carefully you will come to the conclusion that the intended purpose of the manufacturer of the website is to collect information and to support the workflow of the company. This would mean that the website is not a medical device. It would be different if the software would be designed to pre-analyse the images and to calculate sizes of the skin lesions to determine scores or to support the doctors in a different way, directly in the diagnosis.

As to the classification (not just for the web pages) as a medical device, the question whether something can happen is not crucial.

2. Web service as a medical device

A loyal reader of my blog alerted me to a Web service attentive, that provides an API for medical diagnoses: www.programmableweb.com/api/promedas

On the manufacturer's website it states:

Promedas provides a clinical expertise system to medical professionals. The Promedas API can be integrated into existing medical systems that contain a patient file database. Using this data, Promedus can provide a differential diagnosis based on the data contained in a patient’s file. The API is currently in a developer beta. To access the API, contact Promedas.

This immediately results in the first few questions I am asked:

- Is this web service a medical device itself?

- If one integrates this web service into my own software, how must one treat this web service standardly? As SOUP?

- If this web service has a simple GUI, like in the demo / live system, then it can theoretically already be accessed and used worldwide. Does it then have to be automatically designed for all international legal requirements? Even if there was an intended use, which states that the service may only be used in the EU, it would immediately be seen as part of the market observation that it is used in the United States and thus it ought to also meet FDA requirements, right?

The Johner Institute's thoughts on this:

- No, the web service is not a medical device, because it does not serve the diagnosis or treatment of patients, but instead it is an integration into a system that serves the diagnosis or treatment.

- Might be. A SOUP is part of the medical device. Here we are dealing with a data interface, which uses an external service. In terms of risk management, this would of course be assessed.

- When it comes to an exclusion in the intended purpose you would already be off the hook. If an authority stresses because clinics or doctors openly ignore this requirement, you could fix it reasonably well with an IP filtering. However, an authority in Europe has no use in the US and vice versa. Therefore, it would never be active in another area of law.

3. Document Management Systems

The next question is whether document management systems DMS are medical devices. One might argue that patients could be harmed by errors in a DMS. On the other hand, doctors would always make the final decision.

Both considerations are important, but not relevant to the classification as a medical device: Software never damages directly. It's always people or hardware that ultimately hurt or harm patients. What is relevant, however, is what the manufacturer says, as to how customers can and should use the product. If the manufacturer says that the system is used only for documentation, then this system is not a medical device. However, If the manufacturer says that these, for example, X-ray images will be saved for follow ups, the system serves as therapy, making it a medical device as defined by MPG.

Depending on the wording of the purpose, the manufacturer can make a product a medical device or not. Thus the purpose is not just a document. Rather, the manufacturer will document it in many different ways: In the instructions for use, on its website or in marketing materials, at trade fairs and even in conversations.

Therefore, we recommend DMS vendors to articulate clearly. This can also include explicit exclusions of functionality or application scenarios.

4. Hospital information system HIS as a medical device

The task of the clinical information systems (HIS) is obviously to assist users in diagnosing, monitoring and treating patients. These systems occasionally endangering patients (indirectly), is also not unknown. For example, if you

- interchange patient data

- loose data,

- respond very slowly to user input (eg with a malware infestation)

- no longer respond, no longer start, fail completely or

- Information is not forwarded to another system.

Crucial to the question, whether this program should be classified as a medical device, is not only the risk, but being in accordance with the definition:

- A system which is provided purely for documentation or billing, certainly does not fall among them.

- A system that derives diagnoses or treatment recommendations, from entered values, that gives warnings, for example in drug interactions, does fall among them.

Consequences for operators

Because no HIS manufactures will survive in the long run whose systems can't do anything but display entered data, all HIS will - I predict - in the medium-term, become a medical device. But no one wants to hear that, especially not the operators, particularly the hospitals. The reason is obvious: Once a HIS is classified as a medical device, it is subject to the Medical Devices Operator Ordinance. And this requires, for example, that

- Individuals, using the system, must operate and maintain trained. This needs to be documented.

- The system must have regular checks every two years

- After each maintenance operation (software update) all safety-related functions and design features must be examined.

- Etc.

But how can hospitals achieve this? How can they fully check that the HIS with diagnostic functionality still works after a software update? That it still flawlessly cooperates with the RIS, which hangs in the same network segment? That there are no repercussions on the ultrasound machines, which are also connected to the network? The only way to tackle these almost infinite combinations of possible causes of errors, is to operate a risk management system that can be prioritized with the test steps.

Some companies classify their systems as a medical device such as GE whose information system Centricity has the CE mark (in accordance with MDD 93/42 / EC). Here is the corresponding press release from GE.